May 1st, 2021

Systems Change: Mental Models (Collective Narratives)

The more things change, the more they stay the same…does it ever feel that way to you? I know it does for me sometimes! Perhaps, you have been trying for years to see real change happen in an area of social concern. Activating and sustaining change across a complex social issue (system) is no easy feat–but it does and can happen. Systems change work is often defined as, “shifting the conditions that hold a system in place”. If you’d like to learn more about these conditions, check out this seminal work: The Water of Systems Change.

Arguably, the most difficult condition to realise shifts in, is the mental models that exist within a system. Mental models may be defined as the beliefs that people within a system have, about a particular issue. Our mental models shape our attitudes and values, and guide our actions. Changing mental models arguably begins with the slow work of changing collective narratives. But first we need to understand the narratives that are at play within a particular system.

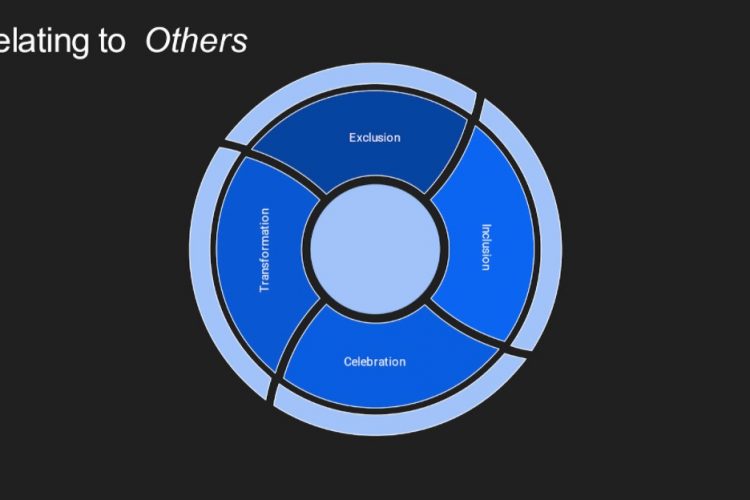

If we wanted to shift the conditions that hold discrimination or bias in place for example, within a system like a school, organisation or community it would be important to first understand the collective narratives, and consider what an alternative ethical narrative (mental model) may be. Take for example the important question: ‘What does it mean to be in an ethical relationship with people who are different to ourselves’? Or we could ask, ‘how do we relate to those with whom we seemingly have nothing in common’? To illustrate this, I give here the example of a school. You’ll see four different mental models that exist when people are in relationships that are different to themselves (the ‘Other’ or the ‘stranger’). The first 3 easily recognisable; the 4th is an alternative narrative.

The first mental model or collective narrative is that of exclusion. In a school you may hear teachers’ say, “You are different to us…you are not welcome here”. Or, “He has a problem. It’s not us. It’s not my teaching”. Exclusion exists often within a culture of fear and leads to the demonisation of the stranger. We exclude those not like us. In schools, we alienate young people who do not fit in/are not like us. Zygmunt Bauman (sociologist) uses the term ‘anthropoemic’ meaning to vomit out the Other, the stranger.

The second mental model we may often recognize is inclusion. You may hear teachers’ say, “You are welcome here, so long as you become like us”. Or, “We are all the same”. Bauman calls this ‘anthropophagic’ meaning devouring/eating the Other, the stranger. Inclusion adapts existing systems to accommodate for people who are different to ourselves…but in a way it is a form of assimilation. Because we are saying what we have is right, this system works. We just need to adapt things so Others can fit in.

The third mental model, I call celebration. We hear people say, “Let’s celebrate our differences together”. Or, “You be you, I’ll be me”. In schools we might see this when different cultures are celebrated. E.g., through festivals. This plays out in many different ways through the collective narrative of celebrating diversity; tolerating difference. The motivation is usually a belief in the rights of others and the right to express your own culture. This perspective comes from a critical social justice framework, and is focused on raising awareness of critical justice issues, and advocating for change.

There is a subtle difference between the third and fourth mental models. The fourth, alternative narrative says, “I see you have something to teach me about what it means to be in this world”. The difference between celebration and transformation is the extent to which the majority culture is altered by their encounter with the Other. Whereas in celebration we may learn a new language, enjoy different festivals and foods; our core beliefs and practices are not altered. Transformation is the idea that there is something to teach us about what it means to be in the world. We are open to the possibility, with humility and a belief that our own knowledge is partial and broken. Transformation is disruptive to our stable sense of self, because it requires a shift in our core beliefs (mental models). It comes often through awkwardness (and a whole raft of other emotions), vulnerability and also through humility.

I suggest here that any deep cultural capability work (and critical consciousness shifts) needs to begin with an understanding of the mental models (collective narratives) that are at play within a system. In the context where you are working toward systems change, what are the mental models that are at play? How do they impact on the system? If you were to construct an alternative narrative, what would it be?

– Judy Bruce | Research Associate, University of Canterbury | Leadership Consultant, Leadership Lab

May 1st, 2021

Systems Change: Mental Models (Collective Narratives)

The more things change, the more they stay the same…does it ever feel that way to you? I know it does for me sometimes! Perhaps, you have been trying for years to see real change happen in an area of social concern. Activating and sustaining change across a complex social issue (system) is no easy feat–but it does and can happen. Systems change work is often defined as, “shifting the conditions that hold a system in place”. If you’d like to learn more about these conditions, check out this seminal work: The Water of Systems Change.

Arguably, the most difficult condition to realise shifts in, is the mental models that exist within a system. Mental models may be defined as the beliefs that people within a system have, about a particular issue. Our mental models shape our attitudes and values, and guide our actions. Changing mental models arguably begins with the slow work of changing collective narratives. But first we need to understand the narratives that are at play within a particular system.

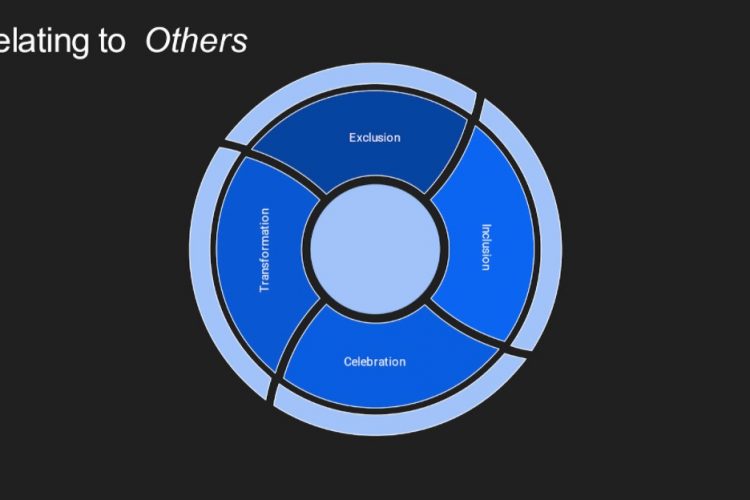

If we wanted to shift the conditions that hold discrimination or bias in place for example, within a system like a school, organisation or community it would be important to first understand the collective narratives, and consider what an alternative ethical narrative (mental model) may be. Take for example the important question: ‘What does it mean to be in an ethical relationship with people who are different to ourselves’? Or we could ask, ‘how do we relate to those with whom we seemingly have nothing in common’? To illustrate this, I give here the example of a school. You’ll see four different mental models that exist when people are in relationships that are different to themselves (the ‘Other’ or the ‘stranger’). The first 3 easily recognisable; the 4th is an alternative narrative.

The first mental model or collective narrative is that of exclusion. In a school you may hear teachers’ say, “You are different to us…you are not welcome here”. Or, “He has a problem. It’s not us. It’s not my teaching”. Exclusion exists often within a culture of fear and leads to the demonisation of the stranger. We exclude those not like us. In schools, we alienate young people who do not fit in/are not like us. Zygmunt Bauman (sociologist) uses the term ‘anthropoemic’ meaning to vomit out the Other, the stranger.

The second mental model we may often recognize is inclusion. You may hear teachers’ say, “You are welcome here, so long as you become like us”. Or, “We are all the same”. Bauman calls this ‘anthropophagic’ meaning devouring/eating the Other, the stranger. Inclusion adapts existing systems to accommodate for people who are different to ourselves…but in a way it is a form of assimilation. Because we are saying what we have is right, this system works. We just need to adapt things so Others can fit in.

The third mental model, I call celebration. We hear people say, “Let’s celebrate our differences together”. Or, “You be you, I’ll be me”. In schools we might see this when different cultures are celebrated. E.g., through festivals. This plays out in many different ways through the collective narrative of celebrating diversity; tolerating difference. The motivation is usually a belief in the rights of others and the right to express your own culture. This perspective comes from a critical social justice framework, and is focused on raising awareness of critical justice issues, and advocating for change.

There is a subtle difference between the third and fourth mental models. The fourth, alternative narrative says, “I see you have something to teach me about what it means to be in this world”. The difference between celebration and transformation is the extent to which the majority culture is altered by their encounter with the Other. Whereas in celebration we may learn a new language, enjoy different festivals and foods; our core beliefs and practices are not altered. Transformation is the idea that there is something to teach us about what it means to be in the world. We are open to the possibility, with humility and a belief that our own knowledge is partial and broken. Transformation is disruptive to our stable sense of self, because it requires a shift in our core beliefs (mental models). It comes often through awkwardness (and a whole raft of other emotions), vulnerability and also through humility.

I suggest here that any deep cultural capability work (and critical consciousness shifts) needs to begin with an understanding of the mental models (collective narratives) that are at play within a system. In the context where you are working toward systems change, what are the mental models that are at play? How do they impact on the system? If you were to construct an alternative narrative, what would it be?

– Judy Bruce | Research Associate, University of Canterbury | Leadership Consultant, Leadership Lab